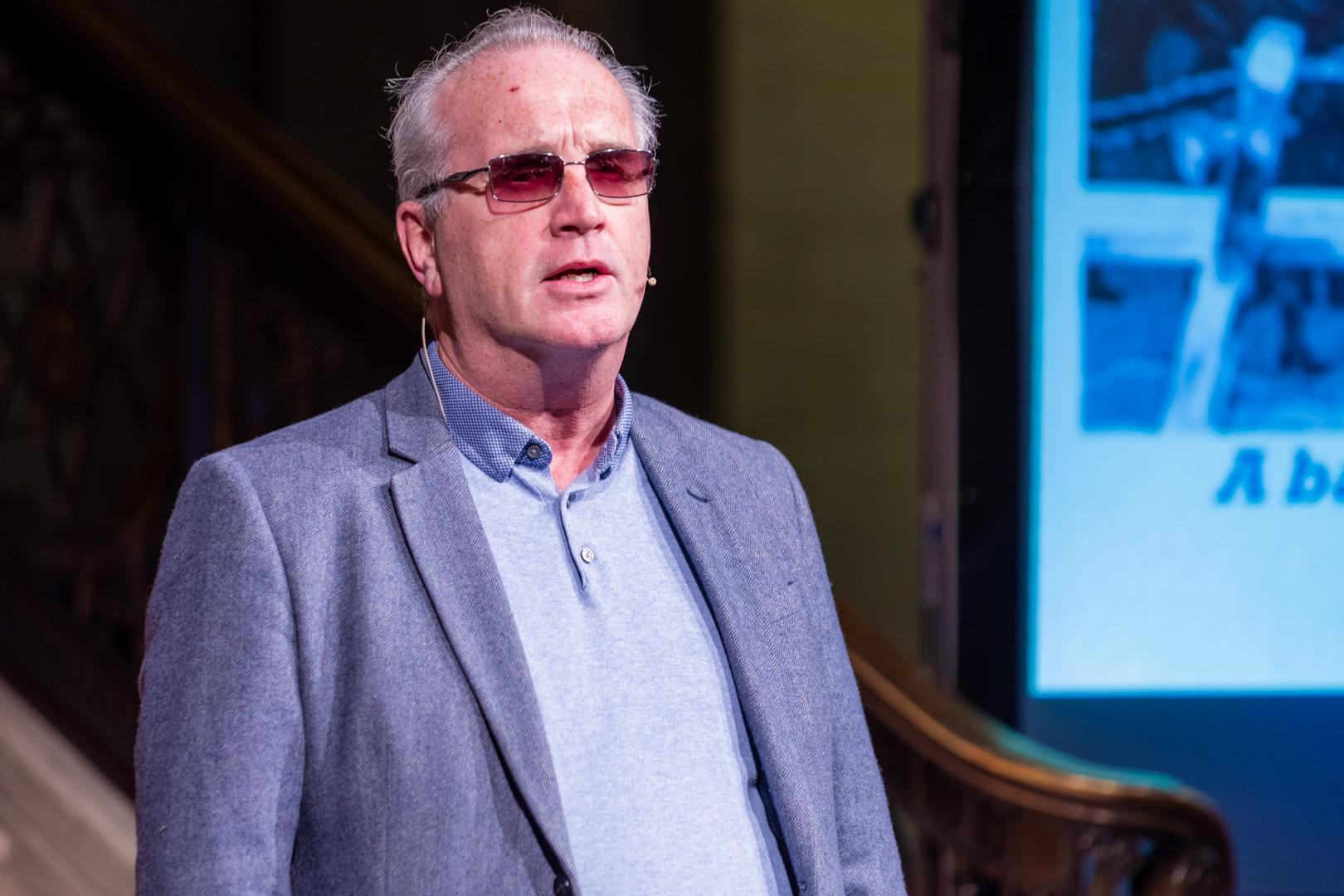

Richard Moore with sunglasses on to cover his blindness. "I got out of school at twenty past three. By half past three, I was lying on the school canteen table."

“I was a happy-go-lucky child,” reflects Richard Moore. “Creggan was a great place to live, I was loving life playing football.

“I was glued to watching Pele play for Brazil in particular. I'd watch him on the TV and then go out play pretending that I was wearing that famous yellow number 10 shirt.

“That was me up until I was shot.”

At twenty past three on the afternoon of Thursday, May 4, 1972, 10-year-old Richard Moore, like the rest of his classmates, ran out of Rosemount Primary School to make his way home.

No doubt his immediate plans were to have a quick kickabout before being called in for his dinner and then resume re-enacting Pele's skills in the backyard with his football.

Unfortunately, there would be no playing football against the fence that day. In fact, he never made it home – not until much, much later.

Having ran past the school exit, there was a tremendous bang. The next thing Richard knew, he was being frantically attended to by his teachers and medics having been shot in the face with a rubber bullet fired by a British soldier, Captain Charles Inness.

While he would survive the shooting, the young Richard would pay a life-changing price as the damage done by the rubber bullet had robbed him of his sight.

Today marks the 50th anniversary of that fateful day. While Richard has fought back with great character and determination to rebuild his life – school grades and a university degree were achieved, a successful pub business was built up with Richard trading that in to set up the Children In Crossfire charity that helps provide an education and basic needs to children in war-torn areas – one can not help but wonder how his life would have panned out had that British soldier not opened fire.

“I was at Rosemount Primary School when I was shot,” said Richard. “It was at the bottom of the school football pitch. The soldier who shot me was on an army lookout post which faced onto the pitch.

“There wasn't really anything, like a battle between the army and the Provos, going on in the area at that point.

“The police station there was a flashpoint to be fair. It was an area where you had shooting and bombing incidents and riots but there was nothing going on that day.

“It was twenty past three in the afternoon and the school was closing for the day – it wasn't like the general public were walking through there. It was a pretty innocuous day as far as I was concerned – just a normal day running home.

“You had to pass that army lookout post on your way home. It was on your right-hand side as you left. There were days when you would look at it and there were days that you didn't. You couldn't get around it and you couldn't go behind it – it was wedged in between the houses at Creggan Hill.

“You didn't even know if the army were unsighted to be honest. You could have went another way home – there was about three or four other ways you could have left school such as via Helen Street, Marlborough Road or the Beechwood shops.

“But you didn't plan what route you took to go home from school – you didn't really play anything at that age. You just ran with the crowd. Somebody might lead the charge and say 'lets go out this way'. That's just the way you went – just pure childhood innocence.

“I remember the army one time saying 'there was a crowd there' – well of course there was. There were a couple of hundred schoolchildren on their way home. It's an interesting topic in a sense. You know, 'what is a skirmish?', 'what justifies firing a rubber bullet at a group of children?'.

“On a different day, I wouldn't have put it past any youngster to lob a brick at the lookout post. However, teachers in those days were no different to now. If a group of children are looking to cause some damage, the teachers are not going to let it happen.

“Our teachers were very aware of the sensitivities around the army and different things around the schools. An army lookout post at the bottom of our school was always potentially an area that youngsters could get interested in – either through curiosity or to shout at it or to lob a brick at it.

“Sometimes I think if the army could just prove there had been three or four children throwing a stone, does that justify the incident? To me it wouldn't.”

Richard cannot remember the moment when he was shot. One minute he was running along out of the school and on his way home, the next he was on a table as others were trying to save his life.

He added: “I got out of school at twenty past three. By half past three, I was lying on the school canteen table.

“I remember seeing all the houses at the back of Creggan Hill by which point, I would have ran towards the route that was where the army lookout post was.

“I just remember approaching the lookout post.... you don't remember the bang or anything. Next thing was, I was lying on that table in the canteen.

“My music teacher, Mr Giles Doherty, had heard the bang. He ran over, lifted me and carried me to the school canteen. I can remember him asking my name and I told him 'my name is Richard Moore'.

“So he got a bit of a shock because he knew me very well but he couldn't really identify me that day because of the extent of my injuries. My nose was completely flattened, my eyeballs were out of their sockets and my face was just a bloody mess.

“I also remember people tugging at me, pulling at my shirt. I discovered afterwards they were cutting off the straps of my schoolbag.

“As I said, I don't remember the bang but I do remember that I was blind from that point on. I was only ten or twelve feet away when the bullet hit me at point-blank range.

“I'm lucky I'm alive. I think of the families of Stephen McConomy – young Stephen was killed by a rubber bullet (in the Bogside area of Derry, 1982) and Julie Livingstone was also killed by a rubber bullet (in West Belfast, 1981).

“I think of them and to be honest, I think if I had been half an inch forward, I would have been killed too.

“I think the bullet came in from the right hand side and hit me on the bridge of my nose. Had I been half an inch further forward, I think the bullet would have hit me on the side of my head.”

Following a period of time in hospital, Richard was allowed to go home where he was finally told that he would never see again. It was a double-blow for his mother, Florrie, who earlier that year, had received news that her brother, Gerry McKinney, had been killed by the British Army on Bloody Sunday.

Richard continues: “It was a month after it happened when I found out. I was at home and my brother took me for a walk up our back garden. He said, 'Richard you know what has happened' and I said 'aye I was shot'. He then asked if I knew what damage was done. I said no I didn't. He said, 'you have lost your right eye and you will never be able to see out of your left eye'.

“There was no such thing as counselling available as it probably would be today. The people that supported me were my family, our neighbours and other people in the Creggan. My mammy and daddy got great peace from the Creggan Chapel and the priests up there.

“My mammy's brother, Gerry McKinney, was shot dead on Bloody Sunday earlier that year.

“For her brother to be shot dead by the British Army in January and then for me to be blinded by the British Army in May.... it was very tough on my mammy. She was just broken. I'm convinced my mammy had a mental breakdown because of all that happened.”

Talks amongst the family began about what to do with Richard and his schooling. After much deliberation, his father Liam made the decision not to send his son away to be a boarder at a special school for the blind in Jordanstown, outside of Belfast.

A decision that years later would end up with Richard making his daddy proud.

Richard said: “I didn't go to a school for the blind. I went back to Rosemount the following September to start Primary Seven. The following year, I went to St Joseph's Secondary School and stayed there until I had done my exams and then went onto Ulster University from there.

“It's a great tribute to those teachers because back in those days, it wasn't the done thing to have a disabled child in the school. Integration wasn't a buzzword then.

“My daddy was the type of man that took advice from people he thought who knew best. He'd listen to advice and tried to make the best decision from that advice.

“There was talk about sending me to a school for the blind. I could hear the talk in the house and to be honest, if they had sent me to such a school – which meant leaving home and going to Jordanstown near Belfast and living there – that would have been more traumatic for me than being shot itself.

“I would have been taken away from my family and friends. I know that's not right for everybody, but it wouldn't have been right for me.

“A lot of educated people were advising my daddy that I should go to the school (in Jordanstown) saying it would be better for me. But then he began to become aware that I didn't want to do it.

“His heart and his head were competing against each other and then he made the decision not to send me to a school for the blind.

“I think he was always worried about 'did I make the right decision for Richard?'. Five years later, I got five grade 1's in my CSE's and the press done a frontpage story on it.

“I remember that day, I was 16 and a typical teenager lying in my bed. My daddy comes up and wakes me up. I was trying to be all cool and disinterested but I was dying to hear what the paper had written.

“My daddy read the paper out to me and it was many years after that – after my daddy was dead – that my brother said to me, 'that day was one of the proudest days for daddy'.

“It meant that he had made the right decision for me not to send me to a school for the blind.”

Richard Moore: "I think any forgiveness that I have has come from my parents.

"Despite the hurt, despite the pain that they experienced, I never heard them say an angry word."

Many years later, and out of the blue, Richard received word of the identity and whereabouts of the soldier who shot him – Charles Inness.

While a number of victims and families of victims during the Troubles have understandably found forgiveness a difficult obstacle to overcome, Richard admits that forgiving Inness for what he had done to him was not a barrier.

“For thirty-three years, I knew nothing about him,” says Richard. “Didn't know his name or anything.

“It wasn't until a TV company called Hotshot Films in Belfast decided to make a documentary of my story. I said to them, as I had said to many journalists over the years, that I would love to meet the soldier some day.

“They just had more success than anybody else in tracking Charles down. What happened next was that I wrote him a letter and three weeks later, he sent one back.

“As part of my letter, I asked him if he would be willing to meet with me. He got back and said he would.

“I flew to Scotland and met Charles for the first time. It was an amazing experience. I said that I forgave him. I understand that for many other people who have suffered, forgiveness is difficult and a lot of people can't give it – especially those who were victims during the Troubles.

“But for me, I think any forgiveness that I have has come from my parents. Despite the hurt, despite the pain that they experienced, I never heard them say an angry word. That's probably down to their own faith.

“That probably had an impact on me to the point where I wanted to meet the soldier and tell him I had no anger towards him.”

While Richard has forgiven Charles Inness and the pair are still in dialogue to this day, he admits that he doesn't agree with Inness' version of events of what happened that day.

However, the continued conversations between the two finally produced something that has meant a great deal to Richard – an apology.

He added: “Charles was a Captain in the army when he shot me. Which was a bit of a shock for me when I found out a few years later. I had built up a mental image of the man who shot me – I thought he might have been an 18-year-old squaddie. A Captain is a bit too highly-ranked to be on the front line.

“Charles eventually retired as a Major. He doesn't sugar-coat anything for me or say things to try and make me feel better. He says how it is from his point of view and I respect that.

“I don't agree with his own analysis of what happened but that's the way life is. To Charles, there was an incident that day and that rubber bullets were harmless. He fired a rubber bullet to get the children to bugger off home basically.

“He would also go on to say that he didn't even see me. He regrets what happened and that with the benefit of hindsight, he would never have fired that rubber bullet. I suppose that's progress.

“It was six years after I first met him that he said 'sorry'. I never asked him to apologise but when the apology came, it was nice.”

Richard, via his Children In Crossfire charity, has gone around the world to promote peace and to help children in areas of conflict – especially those who have been affected by it like he was back in 1972.

He has met with the great and the good – one person in particular stands out. A man who Richard counts as a friend. The Dalai Lama.

“I first met him at an event at St Columb's Park House,” says Richard. “He was speaking at an event there and I was in the audience.

“He started to talk about forgiveness and I remember thinking, 'he is describing exactly how I feel'. I put my hand up and I briefly told him my story. I don't know who organised it but I ended up sitting beside him for my lunch. He began to ask me for the full story of what happened to me.

“He then invited me out to India and that's how it came about. Couple of years later, I met him in Belfast and I had told that – at that stage – we had tracked down the soldier who shot me.

“After I met the soldier, I sent the Dalai Lama a letter to say I had met the soldier. I asked if he would be a keynote speaker at a Children In Crossfire event I was organising in Belfast and he sent a fax back saying he would.

“I pinch myself when I think about the relationship that I have with his Holiness. It's just something that's almost beyond words.

“The Dalai Lama for me is everything that we all should strive to be. He is the embodiment of compassion, peaceful message and forgiveness.

“He says some of the most profound things in the simplest of ways. For him to take a particular shine to me, I just find that incredible.

“I love the fact that he holds me in such high regard because I admire him enormously. At the end of the day, the Dalai Lama is a very ordinary man. He's very grounded and I think that he values people that would in some way re-enforce the message that he tries to put out.

“Although I haven't seen him for a couple of years, when we're together, we get on well. It's a very privileged and hallowed place for me to be in really.”

Subscribe or register today to discover more from DonegalLive.ie

Buy the e-paper of the Donegal Democrat, Donegal People's Press, Donegal Post and Inish Times here for instant access to Donegal's premier news titles.

Keep up with the latest news from Donegal with our daily newsletter featuring the most important stories of the day delivered to your inbox every evening at 5pm.