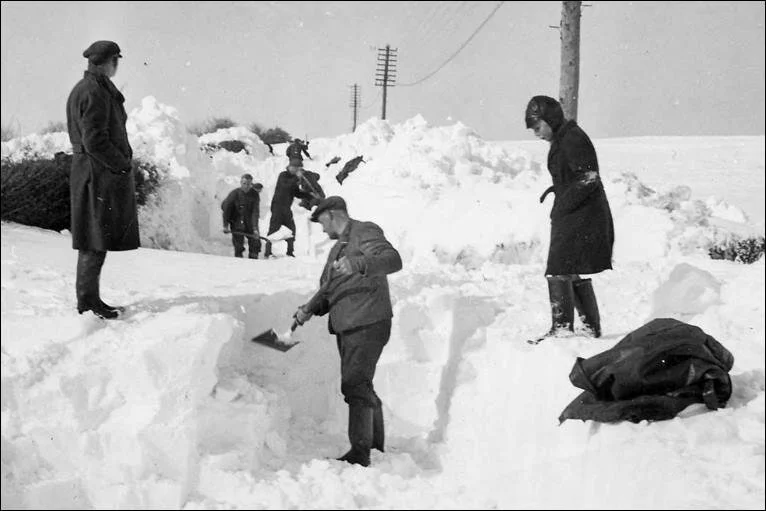

Donegal County Council men were exhausted from shovelling snow – they would do so from the beginning of February until March 17, St Patrick’s Day, when the thaw eventually arrived.

Terrible harvest conditions

Incessant rain fell during the months of August and September 1946, resulting in truly awful harvest conditions. At that time, the compulsory tillage regulations that had been introduced by the government during World War Two were still in place. Farmers were therefore duty bound to cultivate a certain acreage of their holdings. The growing of wheat, for example, was compulsory in order to ensure adequate supplies of flour for bread. The government had rightly decided that, due to the uncertainty of the war, Ireland needed to be self-sufficient.

The result was large swathes of the Irish countryside, ripe with wheat and oats, ready for harvesting in the Autumn of 1946. But there was no getting into the fields. The heavens opened for two months and ground conditions quickly deteriorated to the point where harvesting machinery could not be used.

In the end, the Taoiseach, Éamon de Valera, declared a state of emergency. A concerted campaign was put into place, utilising volunteers, the army, public service staff and local authorities, to save the harvest. Due to the rain, the crop had been battered flat. For the most part harvesting was reduced to manual labour. Armed with scythes, reapers cut the corn and wheat into swathes and it was tied into sheaves. It was backbreaking work, carried out across the country, but thanks to an unprecedented communal effort, a large portion of the harvest was eventually saved.

Those who hadn’t retrieved their harvest by late October 1946 were stopped in their tracks when a fall of snow terminated their efforts. A sign of things to come.

The Big Snow Arrives

Freezing temperatures set in during the final week of January 1947 providing the ideal conditions for what followed. The following week, as January eased into February, dry powdery snow began to fall and continued on and off for many days. Indeed, the Irish Times recorded that most places in Ireland had between 20 and 30 days of snowfall. It was described as “soft and fluffy” and it fell in huge flakes. Very quickly, the countryside became a winter wonderland. Driven by a biting east wind, the snow drifted into every hollow and depression and, as a local newspaper recalled, “the landscape assumed the appearance of a vast white prairie.”

Freezing conditions, which were to last well into March, only made matters worse. Those of us who thought recent cold snaps were inconvenient can only imagine what it must have been like. Here’s a newspaper report from the time:

“Bushes, trees, telephone and power lines disappeared under a massive burden of snow. Freezing temperatures solidified the surface, and it was possible to walk without restriction over submerged trees, pylons and buildings. Roads became impassable, communications were cut off and life in rural districts came to a standstill.”

It really was that bad. Thomas The Miller, from Buncrana, recalled as a boy snow drifts as high as the upstairs window of his home in St Columba’s Avenue. It was the same story all across Inishowen.

Trains, buses, lorries and cars were abandoned in deep snow drifts. Many became buried and wouldn’t be seen again until the thaw several weeks later. Roads were impassable and entrances to houses were only accessible when tackled with spades and shovels. The modern day snowplough had yet to appear on the scene, as had the bulldozer, so roads remained closed. Rivers too were frozen over.

Those farm animals that weren’t in sheds or outhouses fared badly. Large numbers of livestock were lost, buried under snow. Desperate farmers seeking to locate their animals tried to spot them by looking for funnels in the snow caused by the breath of the animal trapped beneath. Some were located and dug out. A lot of sheep were lost on the hills, smothered under the drifting snow.

At times people were actually walking on the tops of hedges when they ventured out for supplies or to go to Mass. All around the country many elderly people succumbed to cold and exposure. Burials proved a particular difficulty due to both the snow and the frozen ground. Coffins were transported on improvised sleighs but in some instances, remains had to be temporarily buried in snow-pits until graves could be located and opened in the frosty ground.

Council men were already exhausted from shovelling snow – they would do so from the beginning of February until March 17, St Patrick’s Day, when the thaw eventually arrived. The story goes that the snow was so high in places that when the men were cutting at the snow with their shovels, they could actually hang their coats on the telephone wires!

All over the country people were dicing with death on a daily basis as they struggled through the worst snowstorm in living memory.

Inishowen was no different. Some of the stories from that time have been passed down from generation to generation.

The townland of Tonduff lies nestled between Dunree Fort and Old Mountain, some seven or eight miles outside Buncrana town. On the first weekend of March 1947, it might as well have been a million miles as far as Nurse McCrudden was concerned. Inishowen was in the grip of the Big Snow, enduring Arctic conditions that even the oldest folk in the peninsula couldn’t recall the likes of. And Nurse McCrudden had just got word at her home in Buncrana of an urgent case of a woman in labour in Tonduff. It would be a journey she would never forget.

A car was out of the question, so she persuaded a lorry owner to make an attempt at the journey. After about a mile and a half the lorry became stuck in the snow. Frantic efforts were made to get it back on the road. Whin bushes were pulled and placed under the wheels for grip but to no avail. There was nothing for it: Nurse McCrudden got her bag and and set out on foot for the remaining five or six miles.

Nurse McCrudden’s Dunree Ordeal

It was a nightmarish ordeal and incredibly dangerous. In places, particularly near Dunree, the snow drifts were between five and seven foot deep. More than once the brave nurse plunged into her waist. On occasion, as she heaved her way through it, the snow was piled so high that she was able to touch the telegraph wires with her hand.

Finally she reached her destination to find that the child had been delivered with the assistance of two neighbours. However the mother was so weak that all in the house were convinced she was dying – indeed they were kneeling at the bedside reciting the rosary. Nurse McCrudden, although exhausted, wet and cold after her exertions, put her medical knowhow to good use and was able to stabilise the patient. Later, she repeated the arduous journey.

Nurse McCrudden’s experience was being replicated all over the peninsula and indeed the country. Europe was blanketed in snow. By the beginning of January 1947 in post-war Germany, hundreds were already freezing to death in -35 degrees of frost. Yet, ten days into January only the hilltops were snowcapped in Inishowen. Heavy rain and mountainous seas off North Inishowen in January preceded the first of the snow blizzards in early February. Within days Inishowen was snowbound. Turf supplies were quickly cut off. By Sunday, February 2, the mountain road between Buncrana and Carn was lying under a foot of snow. Matters were made worse by an influenza outbreak in Carn.

It was towards the end of February that things got particularly bad. Thick blizzards, driven by North-East winds and followed by ferocious frosts became the daily norm. The Brickfield Hole at Burnfoot and the Mintiagh Lakes were frozen over and covered in snow, as was the Mill River in Buncrana. In Derry huge sheets of ice capped the Foyle.

READ NEXT: The story of 'Home to Donegal' and how the song has come to be loved worldwide

By-roads were completely impassable, even for horse traffic. Glentogher, areas around Fahan and the Mintiaghs experienced very deep snow.

Of course children and adults alike did have some fun, and sleighing was indulged in everywhere. Most people had the good sense to stay off the frozen waterways – in Dublin three boys had died as a result of ice breaking on a quarry pond.

Communications with the outside world were particularly difficult. Radio Eireann was the only means of learning what was going on elsewhere but they too struggled to stay on air with storm damage reported at the Athlone transmitter.

Buses often had to be abandoned where they got stuck. Two of the morning buses on the Carn–Derry route only got as far as Glentogher before the road became impassable. A lorry managed to deliver mail to Malin but no buses ran. Farmers were already reporting huge losses of sheep on the Inishowen hills. Water fowl were also dying in huge numbers.

Towards the end of the first week of March, roads in North Inishowen were finally becoming passable. Horses and carts were able – for the first time in weeks – to negotiate their way through to Carn with and for supplies. But it was a false dawn.

Blinding Blizzard Hits Inishowen

Another massive fall of snow hit the north of Ireland on March 12. Inishowen was buried over a period of twelve hours. The blizzard in Buncrana was described as “blinding” and was driven by a sixty miles-per-hour gale. Four to five feet high drifts of snow ran on parallel lines either side of Buncrana Main Street. At the West End a 12ft wall of snow cut off the Cockhill Road. Similar drifts cut off the north of the peninsula. Not a single vehicle of any kind could exit or access Carndonagh.

John A McLaughlin, from Carrowmenagh, remembered the Big Snow as a 15 year-old boy. He was fascinated by the way the snow drifted: “I clearly recall drifts ranging from six to nine feet high. An east wind drove the snow until it hit an obstacle, be it a house or a hedge and it just piled up and up until whatever time the snow stopped. The temperatures were so low that the perfect foundation was laid for the snow to stay.”

Farmers were now desperate. Spring sowing of crops was but an aspiration – ploughing wasn’t even thinkable. The scarcity of fodder was a huge concern with hay supplies exhausted and straw supplies almost out. Turnips were feared to be useless and many potatoes were frosted in the pits.

John A McLaughlin, recalls tending the family potato pit: “It took a pick and shovel to get at the potatoes. And afterwards you spent an age covering the pit up again to keep out the frost.”

Food supplies too were getting scarce – John recalls that supplies of the trademark brown flour of the time were running low.

One hill farmer found sixteen of his sheep drowned in a boghole. There was also huge danger to human life. A 70 year-old Desertegney man by the name of Doherty was found dead in a snowdrift a mere hundred yards from his house. He had gone to fetch fodder for livestock.

All over Inishowen, serious difficulty was experienced in the burial of the dead. The funeral of Mr Michael Grant, the oldest man in the Illies, was held up, as it was impossible to leave from his late residence to St Mary’s Chapel, Cockhill. Two lorry loads of volunteers from Buncrana and others from the Illies worked to cut a passage to facilitate the funeral. The funeral was finally able to take place two days after originally scheduled but not without considerable difficulty. It was reported that some mourners had to “hack a way through the width of their doors” just to leave their houses.

Snowbound Train From Derry

The Buncrana train, en-route from Derry, got as far as Fahan on the night of March 12. There it became embedded in a 7ft snowdrift. Some passengers attempted to complete the three-mile journey to Buncrana on foot but most were forced to turn back.

The marooned passengers – about 50 in total – were finally put up for the night by the caretaker of Lisfannon Golf Club. It is an indication of the ferocity of the blizzard that the relatively short walk from Fahan to Buncrana was nigh impossible.

“That was the toughest job I ever done” – the words of well known Burt man Hughie Whoriskey, speaking some years before his death in 2003. Hughie had just recounted a remarkable adventure which had taken place during the Big Snow.

Hughie worked on the farm of George McNutt at Ballymoney (on the Swilly shore behind Burt Castle) in 1947. McNutt had been ill for over a week and on the night of the March blizzard Hughie was woken at 5:45am to the news that his boss was at death’s door. Hughie ventured the short distance to McNutt’s to find his employer in a bad way: “I’m through, Hughie. If you don’t get a doctor to me today I won’t be here tomorrow.”

It was decided that Hughie would make his way to another farm in the area to dispatch a tractor to the post office at Speenoge to telephone Doctor Weir. The post office hosted the only telephone in the area. When Hughie returned home he found his wife Mary in tears: “She was frantic with worry at the prospect of me setting out in Siberian conditions with driving snow gathered in huge drifts. She got the whole family out of their beds and they started to say the Rosary for my safe return.”

Two hours later, and utterly exhausted, Hughie completed the relatively short journey to the farm of the tractor owner. To his horror the farmer wasn’t prepared to risk his own life or that of his men to make the journey to Speenoge. Like Nurse McCrudden in Buncrana, Hughie had no choice but to set out on foot.

He kept mostly to the fields as the roads were under drifts. He had a sharp iron with him which he used to haul himself out of trouble. Hours later he staggered into Maguire’s Post Office where the call was duly made to the doctor. His nightmare wasn’t yet over. He had to provide “convenience” for the doctor and had no choice but to return to Ballymoney to fetch a horse and cart. Finally, after another hellish journey in and out of fields he met the doctor on the main Derry-Letterkenny road with a rubber-shod horse drawn cart and returned with him to McNutt’s. Just in the nick of time – the doctor said another half hour and the farmer would have been dead. According to Hughie, George McNutt always maintained that he had saved his life.

The Thaw Eventually Comes

Finally, by St Patrick's Day, the temperature rose and a thaw set in. When at last green fields started reappearing, the countryside looked as if it had been hit by a tornado. Power lines and telephone cables lay broken on the ground – it would be months before repairs were completed.

As it happened, the legitimate fears of the farmers were unfounded. Despite the fact that planting was extremely late, the yield from the corn and potatoes crop during the harvest of 1947 was exceptional – perhaps lending some credence to the old theory that frost and snow rid the air and soil of bugs and disease.

Almost eighty years later, and there has never been a storm to surpass the Big Snow.

Subscribe or register today to discover more from DonegalLive.ie

Buy the e-paper of the Donegal Democrat, Donegal People's Press, Donegal Post and Inish Times here for instant access to Donegal's premier news titles.

Keep up with the latest news from Donegal with our daily newsletter featuring the most important stories of the day delivered to your inbox every evening at 5pm.