Now 87 years old, Gonna O’Donnell was born on October 11, 1938 in Ranafast and the Gaeltacht area that shaped him as a fluent Irish speaker.

He was one of nine children, five girls and four boys, three of whom are still alive today. In 1942, during World War Two, he began school at Ranafast Primary, remaining there until 1952. He remembers those years clearly and without bitterness.

READ NEXT: Generations of Donegal Tunnel Tigers - from hand-drilled rock and gelignite to HS2 School was not a place of encouragement or learning. Whether considered smart or slow, children were brutalised equally. Teachers carried three-foot brush handles and used them freely. One incident never left him, a friend called to the blackboard and asked him to point out India on a world map. When he failed, the blow knocked him to the floor. That was education in rural Donegal at the time.

By 14, nearing the end of his schooling, Gonna was offered further education. He declined, having endured enough brutality. Instead, he joined the ESB. Earning £4 & 5s a week, he travelled the Rosses seeking permission from landowners to erect electricity poles. Many refused, fearing the wires would burn their homes. It was enjoyable, sociable work and it offered freedom.

Years later, home on leave from tunnelling work in the early 1960s, Gonna learned that his former teacher was dying. Choosing forgiveness over anger, he went to see him and asked why the children had been treated so harshly. The teacher explained that this was how they themselves had been trained and educated in Dublin. Gonna accepted this explanation and forgave him completely. To this day he holds no resentment, believing they knew no better.

Going Underground into the Noise, the Dust, and the Making of a Tunnel Tiger

In 1956, aged 18, Gonna noticed men returning from Scotland dressed well, pockets full, confidence written all over them.

He decided his future lay elsewhere and boarded the boat from Derry to Glasgow. From there he travelled to the Scottish Hydro Scheme at Killin. His brother Hugh O’Donnell was already there, a leading miner, alongside another Donegal Tunnel Tiger, Hughie Mhaggie, a shift boss. On arrival, Gonna, inexperienced in tunnelling, was handed a pair of wellingtons and sent straight underground.

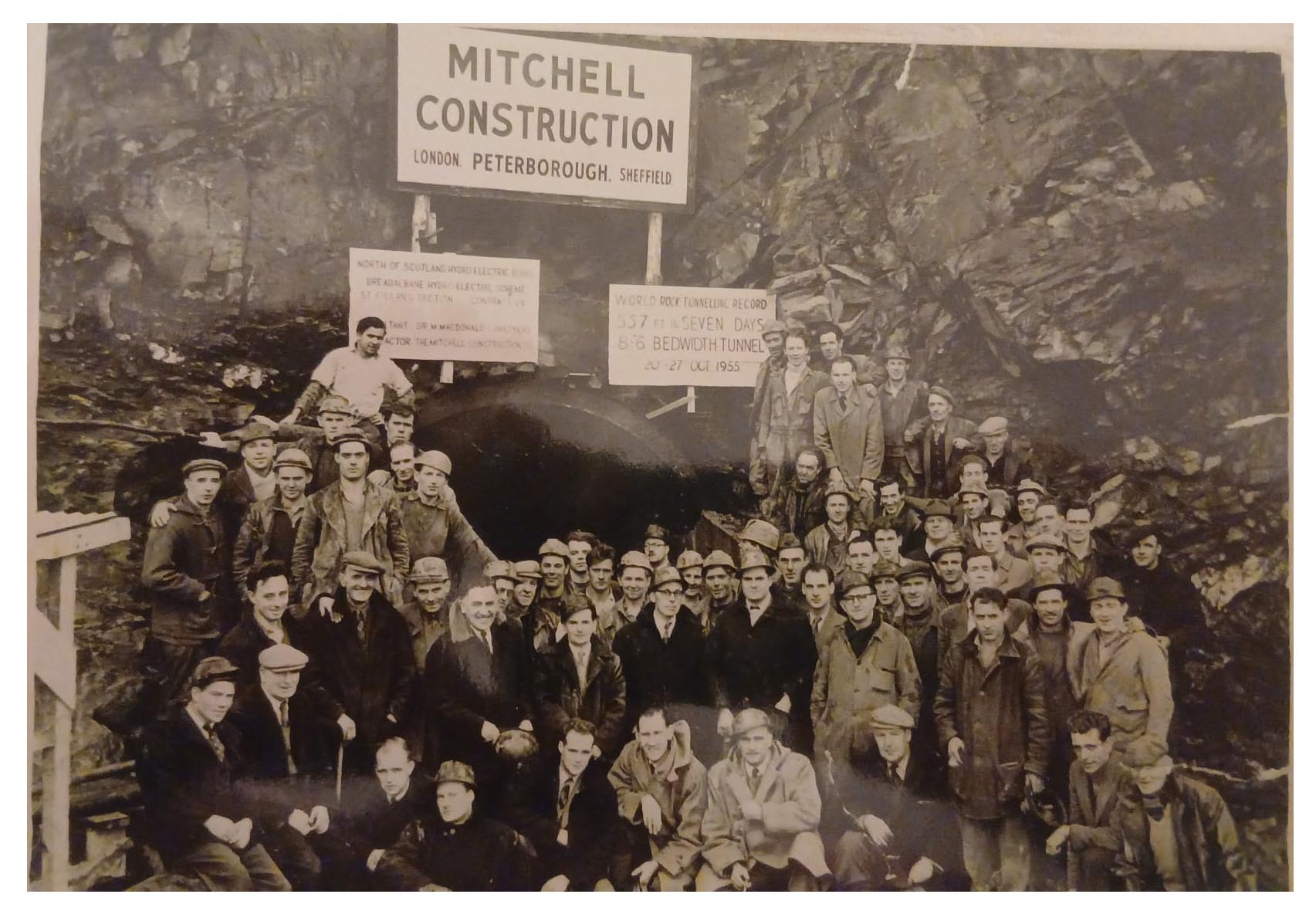

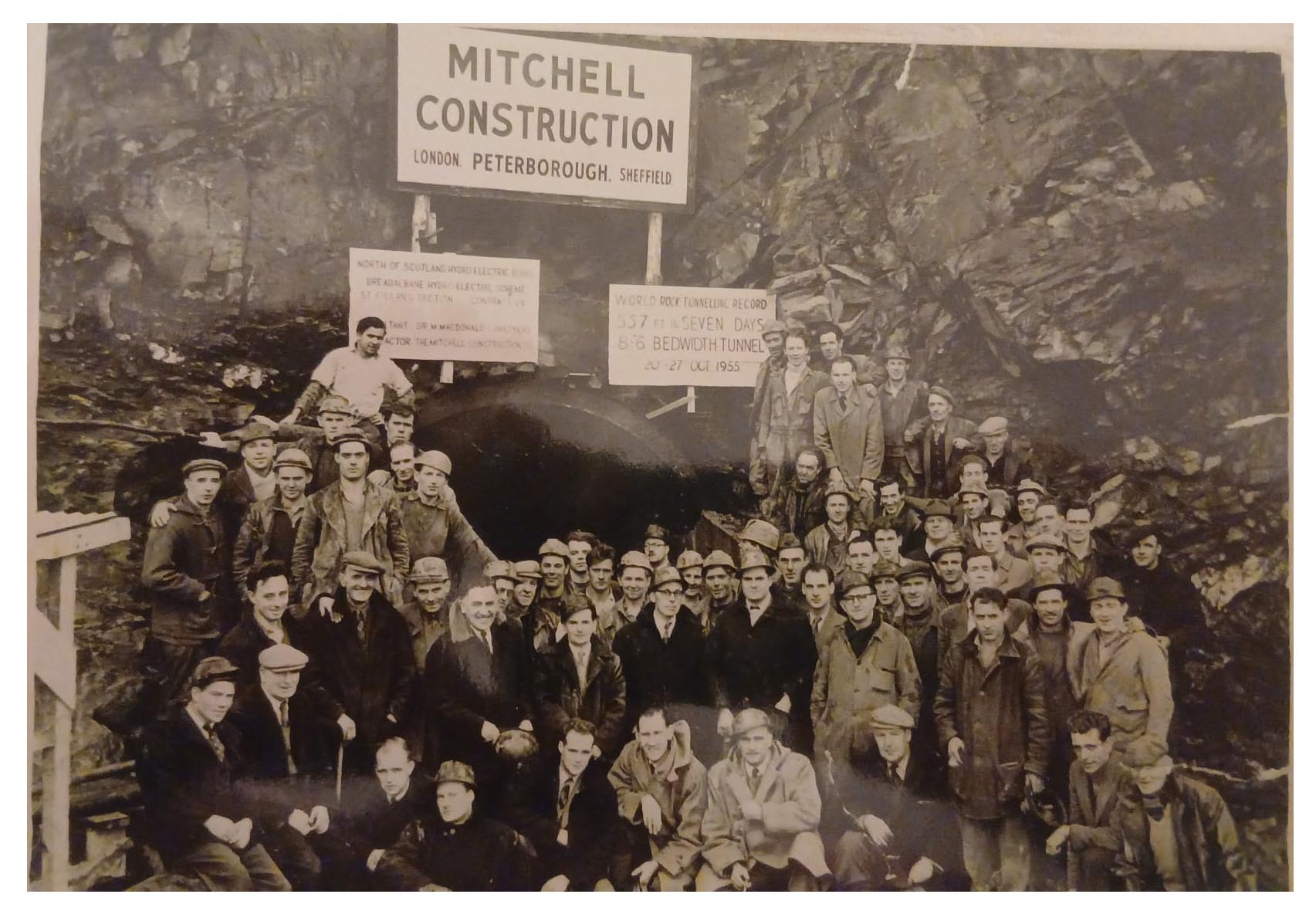

The Donegal Tiger Tunnels who set the 1955 tunnelling record at Breadalbane, photograph provided by Mick Shiels, included in the photograph are his father Neil Shiels and uncles James Shiels and Hughie Shiels, all from Fanad. Mick Shiels was Glasgow based Mulroy Gaels Player of the year six times

The Donegal Tiger Tunnels who set the 1955 tunnelling record at Breadalbane, photograph provided by Mick Shiels, included in the photograph are his father Neil Shiels and uncles James Shiels and Hughie Shiels, all from Fanad. Mick Shiels was Glasgow based Mulroy Gaels Player of the year six times

He entered a world of relentless noise, choking dust, smoke, and danger. The tunnels were driven through hard Scottish rock. He worked in a twelve-man team, all Donegal Tunnel Tigers. The bond between them was unspoken but absolute. Conversation was impossible, drowned out by eight air-driven rock drills screaming day and night. They were driving a fourteen-foot diameter tunnel, drilling eighty holes, each eight feet deep, before packing them with gelignite and blasting. After every explosion, the tunnel vanished into darkness, smoke, and dust.

As one Tunnel Tiger said, “they ate more dust than dinners”. There was no personal protective equipment. Twelve-hour shifts, seven days a week, were normal. £15 a week sterling was good money, but it came at a cost. Today Gonna wears two hearing aids, the result of years spent in that thunderous underground world. Overall, hundreds of miles of tunnels were driven through Scotland’s rock to power the hydro schemes.

Seeking Better Money and Finding Tragedy Underground

After three years, word spread that better money could be earned in Wales. In 1959, aged twenty-one, Gonna travelled to Tonypandy, the hometown of boxing champion Tommy Farr. He knocked on the first door he came to looking for lodgings and was taken in. He later recalled the Welsh as exceptionally friendly and considerate people. Between 1959 and 1965 he earned £25 a week. The work remained drill and blast tunnelling to expose coal, but conditions were improved, with showers, shorter eight-hour shifts, and the comfort of returning home clean.

By 1965, talk again turned to better conditions, this time in Kent, and Gonna headed south. While working in Dungeness, news broke of the 1966 Aberfan disaster in Wales, close to where Gonna had previously worked. A total of 144 people, most of them schoolchildren, were killed when negligently stockpiled mining and tunnelling waste slid down an embankment, destroying homes and burying the local school.

Gonna’s friend Ownie Annie Eoghain Mhoir had remained in Wales and helped recover the bodies. He later told Gonna how he and other Tunnel Tigers dragged children’s bodies from the waste material. The tragedy shook Gonna deeply and left a lasting mark on his generation.

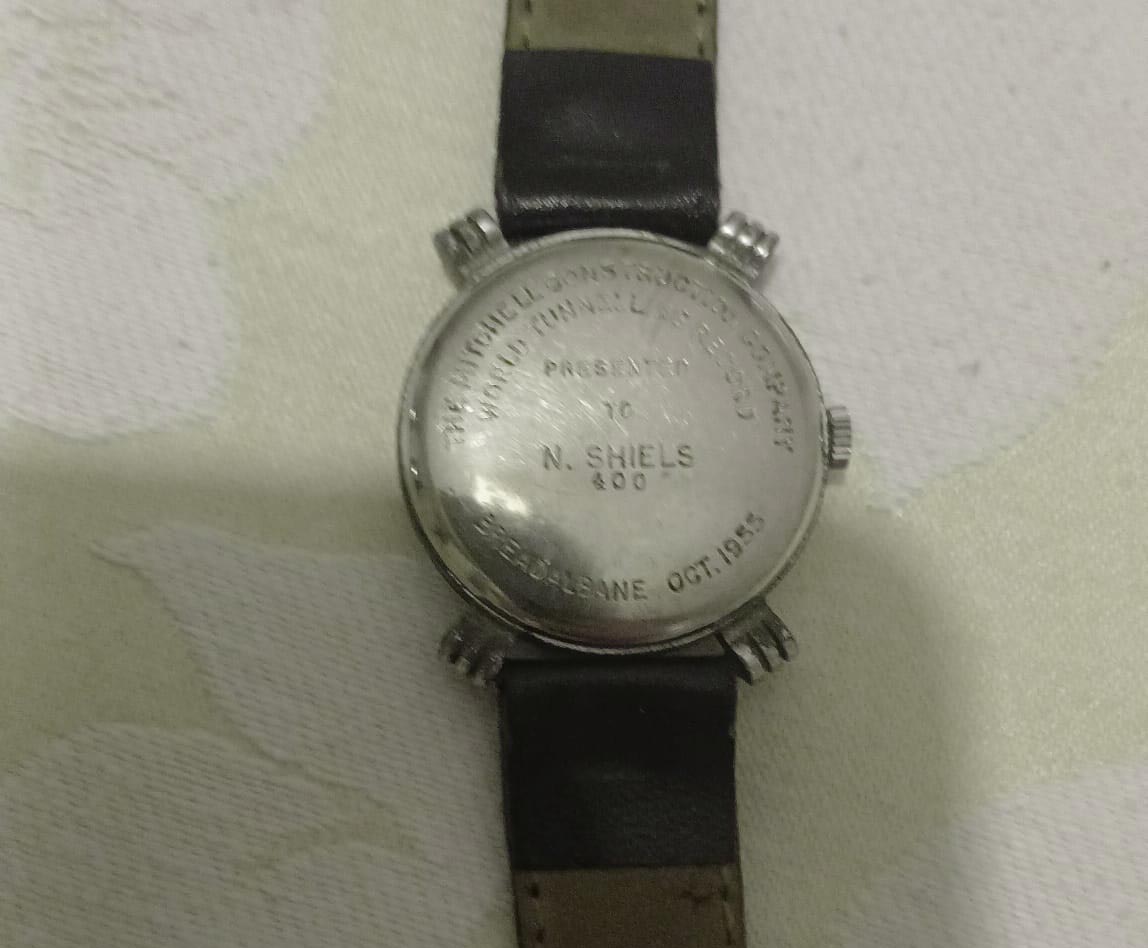

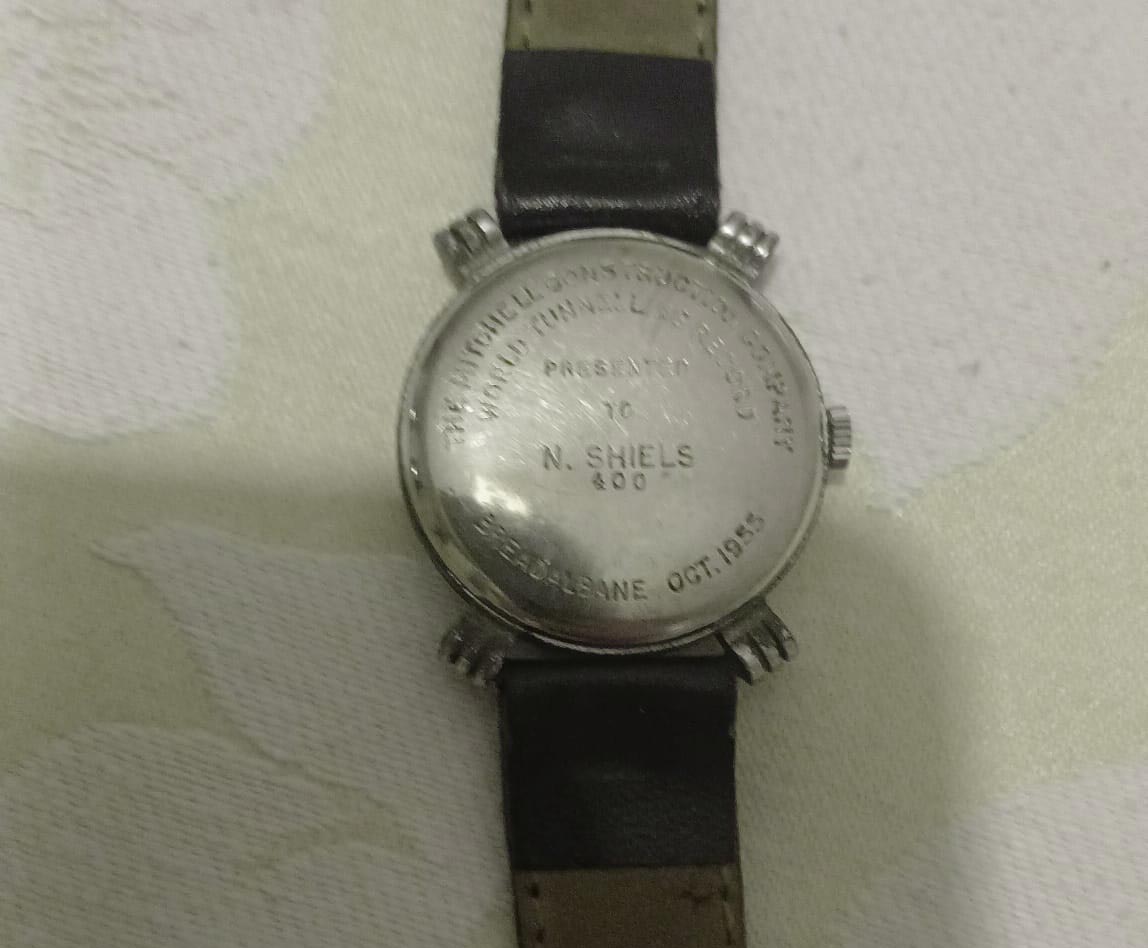

1955 Watch presented to Neil Shiels, Breadalbane Tunnelling World Record

1955 Watch presented to Neil Shiels, Breadalbane Tunnelling World Record

Crushed by Pressure, Living and Dying in Compressed Air

Between 1965 and 1970, Gonna worked on projects in Dungeness, Hunterston, and the Clyde Tunnel in Glasgow. These were the hardest years. Compressed air tunnelling pushed men beyond their limits. He witnessed teammates suffering agonising ear pain and the bends. In compression chambers he saw grown men screaming to be released back to normal pressure. Some never came back out. Health and safety was poor and many Donegal men paid with their lives. Gonna endured five years of this work and survived. He earned £75 a week and sent most of it home to support his family in Donegal.

From the Depths of Danger to a Hard Earned Homecoming

In 1971, he joined Rockfall Construction Limited, blasting the seabed at Howth Harbour in Dublin to allow large trawlers access. The work coincided with a sudden and severe storm that struck Dublin without warning, battering the coastline and causing widespread damage, with chimneys blown from houses across the city. Working from barges in a violent Irish Sea, on one night they were fortunate to make it back into the harbour. Drilling vertically into solid rock and packing it with gelignite, Gonna faced the full force of the waves, drawing on every skill learned underground in Scotland and Wales.

Later that year he joined Donegal County Council, where he remained until retirement in 2004. Repairing water leaks across the county, it was work he genuinely enjoyed, safe, steady, and far removed from the danger that had defined his earlier life.

Looking back, Gonna says he would do it all again. The danger was real and the conditions brutal, but the friendships were unbreakable and the experience priceless. Many of his Tunnel Tiger friends did not survive. Gonna did, returning home to Donegal in 1971 after fifteen punishing years underground.

Donegal Tunnel Tigers at the opening of the Pitlochry Visitors Centre in 2017 along with Scotland’s First Minister Nicola Sturgeon

Donegal Tunnel Tigers at the opening of the Pitlochry Visitors Centre in 2017 along with Scotland’s First Minister Nicola Sturgeon

In 2017, Gonna stood once more among his fellow Donegal Tunnel Tigers at the opening of the Pitlochry Visitor Centre. There he met Scotland’s First Minister Nicola Sturgeon, who acknowledged the hardship they endured, the danger, sacrifice, and lives lost, and assured him their contribution would never be forgotten.

During his years in Scotland, Gonna learned of early 20th century labourers who walked miles into remote mountain sites to build reservoirs and dams in freezing conditions. Many never made it home, dying en route from exposure, accidents, and exhaustion. Some were buried close to the works in graves with no markings, including near Blackwater Dam at Kinlochleven, silent reminders of the human cost behind Scotland’s hydro power legacy.

Gonna says he has told his story as best he can. Much of what he endured, saw, and heard will never truly be told. Still, if given the chance, he would do it all over again.

Today, Gonna lives happily with his wife at Beal na Croite in the Rosses, and is regularly visited by his daughters Evelyn and Rosie. The interview with Gonna lasted two hours and was conducted entirely in Irish.

Eamonn Coyle is a Chartered Engineer and Chartered Environmentalist