In the summer of 2025, images were shared of a scene in Tanzania’s Serengeti National Park – a large group of jeeps and dozens of tourists standing outside taking pictures of ‘The Great Migration’ and blocking wildebeests’ traditional crossing point. While jeep traffic jams have been widely reported in other parks, including Sri Lanka’s Yala, known for its high density of leopards.

Demand is growing rapidly in the safari sector, and now more than ever, attention is being brought to how wildlife experiences are handled by tour operators and holiday companies.

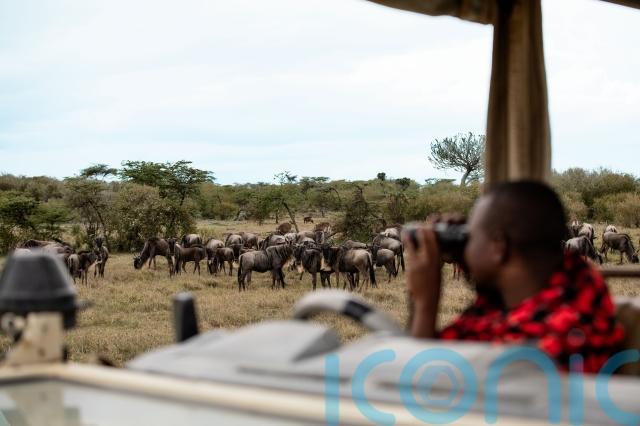

“During the migration up in East Africa, there was a real spotlight put on a couple of places,” says Karl Langdon, conservation and regional director Africa, overseeing Virgin Limited Edition’s safari properties. “It’s crazy. You can get anything between 20 and 60 vehicles trying to get to a crossing to see these poor animals. Just crossing this river on their own is a hard thing, let alone trying to get around all these vehicles and everybody jostling for space.”

Sustainability specialist from Explore Worldwide, Hannah Metheven, points out that “it goes without saying that the wildlife population doesn’t automatically rise in line with this demand – which in turn creates extra pressure on certain hotspots.

“One of the key risks is overcrowding at sightings, which can result in vehicles getting too close and staying too long in order to achieve the ‘perfect shot’. This is exactly what happened last summer, when a video of crowds at the Serengeti went viral – with the welfare of animals clearly second to that of getting a perfect picture.”

Getting too close, making noise and feeding animals can disrupt natural behaviours and cause real physical and mental stress to wildlife, she adds. “These disruptions often go unnoticed but have lasting impacts, especially during key seasonal behaviours that are instinctive and vital to survival.

“Many people simply don’t realise the consequences their presence can have – or how quickly a ‘once-in-a-lifetime’ moment for a traveller can become a daily stressor for wildlife.”

And that’s one of the pressures, perhaps, that an African safari is, for many tourists, indeed a bucket-list holiday – and therefore it comes with an anxiety (and even expectation) to ‘tick off’ spotting what’s known as the Big Five, i.e. lion, leopard, rhino, elephant and buffalo.

South African Langdon, who has lived his “whole life in the bush” says as a guide, “You need to get people interested and get that ‘feeling’ that you get in Africa and when you’re in the bush, it is a feeling. It’s certainly not a tick list, but it’s an emotional attachment.

“It’s not about ticking off the big five, if that happens, wonderful. What’s important, though, is that they get a connection, and if they get that connection, I can promise you that person will be returning to Africa.

“For me, the biggest joy in the magic lies in everything from the plants to the butterflies to the flowers, all the way through to a majestic big bull elephant and you’re just sitting in his company,” he adds.

Safari goers must be a ‘witness’ only. “We adhere to very strict protocols, from how many vehicles in, when you can follow… if an animal’s hunting, you switch off your vehicles, you turn the lights off. You really are there as an observer.”

He suggests staying for a minimum of three nights on safari, to alleviate the pressure to see as much as possible in a short space of time. “That’s when you’ve connected, you’re not going to do that in a day.”

Safari companies and lodges can’t work in isolation though.

Justin Francis, co-founder and executive chair of Responsible Travel, points out: “Safaris have enormous potential to create lasting positive impacts for conservation, endangered species, and local communities. But there are also businesses that have driven indigenous and local peoples off their land, exploited tribal cultures and disturbed wildlife behaviours.”

It’s key that local communities actually benefit from safari tourism. “The best will go beyond this ensuring local people are engaged in any decision-making. They might use community-owned lodges, lease land from indigenous landowners or train local people to take on managerial positions,” says Francis.

“Exploitation of Maasai and other Indigenous cultures is rife, and there needs to be a long-term partnership led by the local community to ensure a genuine, mutually beneficial cultural exchange takes place.”

Langdon adds: “Conservation is certainly not just about fauna and flora in the area. It’s very much to do with local communities and the land that you’re operating in. We work very, very closely with the local Maasai tribes. We haven’t taken the land from the Maasai – we lease it. They, obviously, utilise this land with their cattle. We haven’t stopped that either.”

While there are ethical ways that operators can involve local communities, be wary of visits to tribal villages, and what could be interpreted as voyeurism. For example, Langdon says, “a community tour where you go around and look at people’s homes and see what they eat. It’s always bothered me”.

So how else do holidaymakers ensure what they’re booking is ethical?

Crucially, there’s “no way to guarantee” any particular wildlife sightings on safari, warns Francis. “If a company is promising you’ll see certain animals, I’d be wary.”

Langdon agrees: “You cannot go to a place if they have guaranteed you a big five or a hunt or kill – that’s a red flag. You’re in these animals’ spaces, and we are here to observe, not to manipulate and not to cause any chaos just for tourism.”

Animal interactions – including petting, riding or selfies – are a big no-no .

Langdon says: “Unfortunately, [some places] are breeding lions, just so that people can have a 10 or 15, minute interaction with a lion cub. Once the lion cub gets to a year old, you can’t do anything other than release it back into a cage and never out into the wild.”

Francis suggests asking questions of the company you’re considering – “Is minimising disturbance to the wildlife you’re watching a priority for them? Are they going to turn around when too many other tourists are crowded around a lion? Or are you going to end up in one of those jeeps jostling for space by the river?”

Look for companies that have clear guidelines on how to approach and watch wildlife responsibly. “Some now offer electric vehicles which are quieter than the traditional safari jeep, causing less disturbance to the animals with the bonus of a lighter safari carbon footprint,” he adds.

And don’t be afraid to ask questions. “Ask whether a lodge runs on solar power, what percentage of their staff are from local communities, and how much of your money goes directly to conservation.”

Thankfully, an ethical safari doesn’t necessarily mean top tier prices. “There are amazing, little places that are around, that are family, run and small,” says Langdon. “I know many entry level camps, even down to a backpacker level, that practice the sustainability side.

But look for established organisations. “You can easily get people who are there just for the money, but they’re not going to last very long,” he says. If somebody’s been operating for “10 years or longer”, there’s more chance they’ll be operating ethically.

Subscribe or register today to discover more from DonegalLive.ie

Buy the e-paper of the Donegal Democrat, Donegal People's Press, Donegal Post and Inish Times here for instant access to Donegal's premier news titles.

Keep up with the latest news from Donegal with our daily newsletter featuring the most important stories of the day delivered to your inbox every evening at 5pm.