Dick Cheney, the former vice president of the United States, has died aged 84.

He died on Monday night due to complications of pneumonia and cardiac and vascular disease, his family said in a statement.

“For decades, Dick Cheney served our nation, including as White House Chief of Staff, Wyoming’s Congressman, Secretary of Defence, and Vice President of the United States,” the statement said.

“Dick Cheney was a great and good man who taught his children and grandchildren to love our country, and to live lives of courage, honour, love, kindness, and fly fishing. We are grateful beyond measure for all Dick Cheney did for our country.

“And we are blessed beyond measure to have loved and been loved by this noble giant of a man.”

The hard-charging conservative became one of the most powerful and polarising vice presidents.

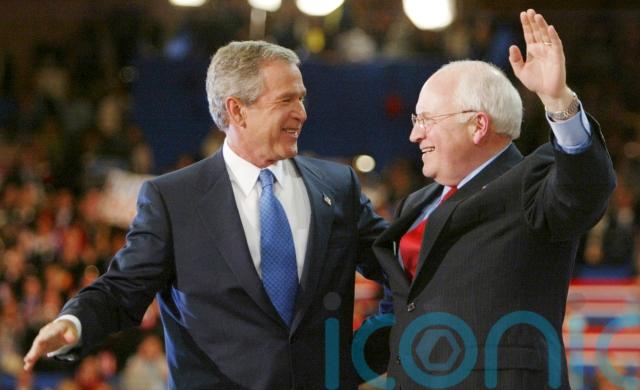

The quietly forceful Mr Cheney served father and son presidents, leading the armed forces as defence chief during the Persian Gulf War under President George HW Bush before returning to public life as vice president under Mr Bush’s son, George W Bush.

Mr Cheney was, in effect, the chief operating officer of the younger Mr Bush’s presidency.

He had a hand, often a commanding one, in implementing decisions most important to the president and some of surpassing interest to himself — all while living with decades of heart disease and, post-administration, a heart transplant.

Mr Cheney consistently defended the extraordinary tools of surveillance, detention and inquisition employed in response to the terrorist attacks of September 11 2001.

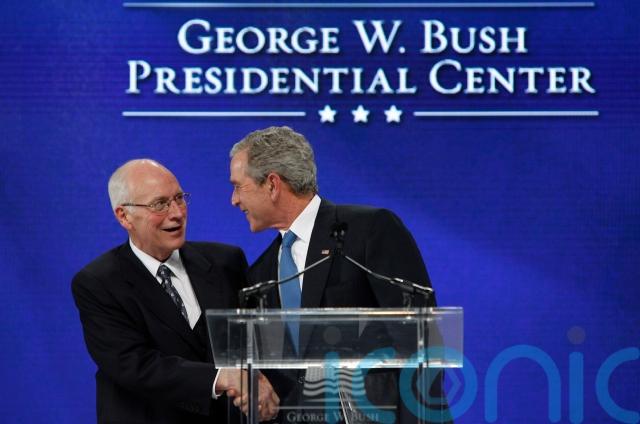

George W Bush called Mr Cheney a “decent, honourable man” and said his death was “a loss to the nation”.

“History will remember him as among the finest public servants of his generation — a patriot who brought integrity, high intelligence, and seriousness of purpose to every position he held,” Mr Bush said in a statement.

Years after leaving office, he became a target of President Donald Trump, especially after his daughter Liz Cheney became the leading Republican critic and examiner of Mr Trump’s desperate attempts to stay in power after his election defeat and his actions in the January 6 2021 riot at the Capitol.

In a television advert for his daughter, Mr Cheney said: “In our nation’s 246-year history, there has never been an individual who was a greater threat to our republic than Donald Trump.

“He tried to steal the last election using lies and violence to keep himself in power after the voters had rejected him. He is a coward.”

In a twist the Democrats of his era could never have imagined, Dick Cheney said last year he was voting for their candidate, Kamala Harris, for president against Mr Trump.

A survivor of five heart attacks, Mr Cheney long thought he was living on borrowed time and declared in 2013 that he awoke each morning “with a smile on my face, thankful for the gift of another day”, an odd image for a figure who always seemed to be manning the ramparts.

His vice presidency was defined by the age of terrorism and Mr Cheney disclosed that he had had the wireless function of his defibrillator turned off years earlier out of fear that terrorists would remotely send his heart a fatal shock.

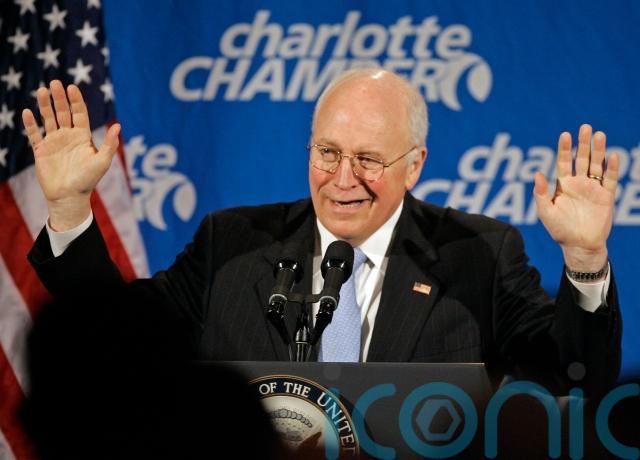

In his time in office, the vice presidency was no longer merely a ceremonial afterthought.

Instead, Mr Cheney made it a network of back channels from which to influence policy on Iraq, terrorism, presidential powers, energy and other cornerstones of a conservative agenda.

Fixed with a seemingly permanent half-smile – detractors called it a smirk – Mr Cheney joked about his outsize reputation as a stealthy manipulator.

“Am I the evil genius in the corner that nobody ever sees come out of his hole?” he asked. “It’s a nice way to operate, actually.”

A hard-liner on Iraq who was increasingly isolated as other hawks left government, Mr Cheney was proved wrong on point after point in the Iraq War, without ever losing the conviction that he was essentially right.

He alleged links between the 2001 attacks against the United States and pre-war Iraq that didn’t exist.

He said US troops would be welcomed as liberators; they weren’t.

He declared the Iraqi insurgency in its last throes in May 2005, back when 1,661 US service members had been killed, not even half the toll by war’s end.

For admirers, he kept the faith in a shaky time, resolute even as the nation turned against the war and the leaders waging it.

But well into George W Bush’s second term, Mr Cheney’s clout waned, checked by courts or shifting political realities.

Courts ruled against efforts he championed to broaden presidential authority and accord special harsh treatment to suspected terrorists.

His hawkish positions on Iran and North Korea were not fully embraced by the president.

Mr Cheney operated much of the time from undisclosed locations in the months after the 2001 attacks, kept apart from George W Bush to ensure one or the other would survive any follow-up assault on the country’s leadership.

With the president out of town on that fateful day, Mr Cheney was a steady presence in the White House, at least until Secret Service agents lifted him off his feet and carried him away, in a scene the vice president later described to comical effect.

From the beginning, Mr Cheney and George W Bush struck an odd bargain, unspoken but well understood. Shelving any ambitions he might have had to succeed Mr Bush, Mr Cheney was accorded power comparable in some ways to the presidency itself.

That bargain largely held up.

Dave Gribbin, a friend who grew up with Mr Cheney in Casper, Wyoming, and worked with him in Washington, once said: “He is constituted in a way to be the ultimate number two guy. He is congenitally discreet. He is remarkably loyal.”

As Mr Cheney put it: “I made the decision when I signed on with the president that the only agenda I would have would be his agenda, that I was not going to be like most vice presidents — and that was angling, trying to figure out how I was going to be elected president when his term was over with.”

His penchant for secrecy and backstage manoeuvring had a price.

He came to be seen as a thin-skinned Machiavelli, orchestrating a bungled response to criticism of the Iraq war.

And when he shot a hunting companion in the torso, neck and face with an errant shotgun blast in 2006, he and his coterie were slow to disclose that extraordinary turn of events.

The vice president called it “one of the worst days of my life”.

The victim, his friend Harry Whittington, recovered and quickly forgave him. Comedians were relentless about it for months. Mr Whittington died in 2023.

When George W Bush began his presidential quest, he sought help from Mr Cheney, a Washington insider who had retreated to the oil business, to find a vice presidential candidate.

Mr Bush decided the best choice was the man picked to help with the choosing.

Together, the pair faced a protracted 2000 post-election battle before they could claim victory. A series of recounts and court challenges — a tempest that brewed from Florida to the nation’s highest court — left the nation in limbo for weeks.

Mr Cheney took charge of the presidential transition before victory was clear and helped to give the administration a smooth launch despite the lost time.

In office, disputes among departments vying for a bigger piece of the constrained budget came to his desk and often were settled there.

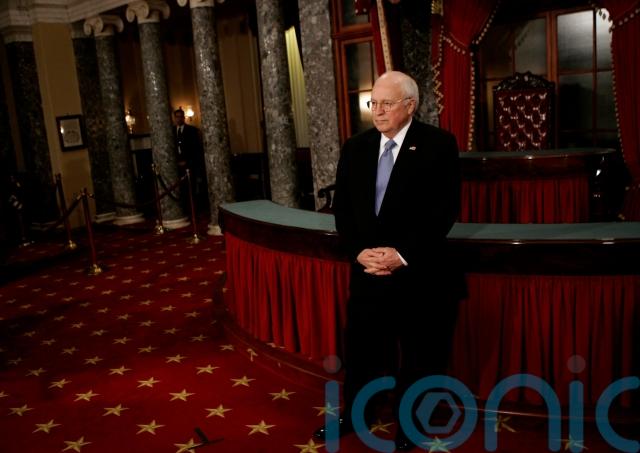

On Capitol Hill, Mr Cheney lobbied for the president’s programmes in halls he had walked as a deeply conservative member of Congress and the number two Republican House leader.

Jokes abounded about how Mr Cheney was the real number one in town; George W Bush didn’t seem to mind and cracked a few himself.

But such comments became less apt later in Mr Bush’s presidency as he clearly came into his own.

Mr Cheney retired to Jackson Hole, not far from where Liz Cheney, a few years later, bought a home, establishing Wyoming residency before she won his old House seat in 2016.

The fates of father and daughter grew closer, too, as the Cheney family became one of Mr Trump’s favourite targets.

Mr Cheney rallied to his daughter’s defence in 2022 as she juggled her lead role on the committee investigating what happened on January 6 with trying to get re-elected in deeply conservative Wyoming.

Liz Cheney’s vote for Mr Trump’s impeachment following the insurrection earned her praise from many Democrats and political observers outside Congress.

But that praise and her father’s support did not keep her from losing badly in the Republican primary, a dramatic fall after her quick rise to the number three job in the House Republican leadership.

Politics first lured Mr Cheney to Washington in 1968, when he was a congressional fellow. He became a protege of Republican Donald Rumsfeld, serving under him in two agencies and in Gerald Ford’s White House before he was elevated to chief of staff, the youngest ever, at aged 34.

Mr Cheney held the post for 14 months, then returned to Casper, where he had been raised, and ran for the state’s single congressional seat.

In that first race for the House, Mr Cheney suffered a mild heart attack, prompting him to crack that he was forming a group called “Cardiacs for Cheney”.

He still managed a decisive victory and went on to win five more terms.

In 1989, Cheney became defence secretary under the first President Bush and led the Pentagon during the 1990-91 Persian Gulf War that drove Iraq’s troops from Kuwait.

Between the two Bush administrations, Mr Cheney led Dallas-based Halliburton Corp, a large engineering and construction company for the oil industry.

Mr Cheney was born in Lincoln, Nebraska, the son of a long-time agriculture department worker.

Senior class president and football co-captain in Casper, he went to Yale on a full scholarship for a year but left with failing grades.

He moved back to Wyoming, eventually enrolled at the University of Wyoming and renewed a relationship with high school sweetheart Lynne Anne Vincent, marrying her in 1964.

He is survived by his wife, by Liz and by a second daughter, Mary.

Subscribe or register today to discover more from DonegalLive.ie

Buy the e-paper of the Donegal Democrat, Donegal People's Press, Donegal Post and Inish Times here for instant access to Donegal's premier news titles.

Keep up with the latest news from Donegal with our daily newsletter featuring the most important stories of the day delivered to your inbox every evening at 5pm.